Monday, April 27, 2020

“Example is the school of mankind, and they will learn at no other.”

— Edmund Burke

If you’re reading this, I assume you’ve already been recruited into one of the several armed motorcycle gangs that scours the city’s ruins for canned food. I know finding a generator to recharge your laptop isn’t easy so I’ll keep this short.

Oh, wait. That’s the first paragraph of the post I’m writing for June. Where’s my end of April post? Oh, here. Let’s start over.

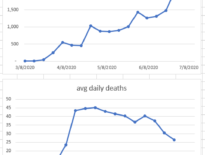

In Los Angeles we seem to have achieved a stalemate with the virus. The number of new daily cases and the number of new daily deaths aren’t going up exponentially, but they’re not going down exponentially either. Both graphs are bouncing around in the same range. Hospital censuses are also neither exploding nor decaying like any well-behaved exponential function should. Hospital beds, ICU beds and ventilators remain available to those who need them. That, in itself, is a major achievement. The curve is flattened, which after all was the first goal of our response.

Now our collective minds are obsessed with two questions. What’s the next step? And how does this nightmare eventually end?

Let’s consider the second question first. What does the final goal look like? We’re currently pinning our hopes on the development of a vaccine or on acquiring herd immunity.

There will certainly be lots of resources, brains, and time devoted to finding a vaccine for the novel coronavirus. But vaccines for coronaviruses are notoriously difficult to develop. The SARS outbreak of 2002 was caused by a coronavirus and led to a search for a vaccine. There still isn’t one. But that outbreak was tiny compared to the current pandemic. Surely, the global search for an effective vaccine will be successful this time. Well, I hope so. But if you need an example of a virus for which a search for a vaccine consumed many dollars and many minds for many years and remains unsuccessful, look no further than HIV.

And what about herd immunity? Herd immunity is the mechanism by which many immune individuals (the herd) protect the other vulnerable individuals from infection. They do so by simply providing the virus fewer vulnerable hosts. If a high enough fraction of the population is immune so that, on average, each infected person infects fewer than one vulnerable person, then the epidemic fizzles out. The goal is similar to the goal of social distancing – put fewer vulnerable people next to infected people – but instead of distance we use immune people as the barrier.

No one is sure how many of us need to be immune for that to happen. 30% is the lowest estimate. Other experts say 50 to 60%. Are we close to that? A study by USC and the LA County Dept of Public Health tested a random sample of LA County residents for antibodies to the novel coronavirus. It found that about 4% of us have the antibody. This was touted as good news since it’s 20 times greater than the number of cases diagnosed through the viral swabs. That implies that the fatality rate of the virus is 20 times lower than we thought, and it underscores that many cases have such mild symptoms they never seek medical attention. A similar study in Santa Clara County found an antibody prevalence of about 3%. Neither of these studies has been peer-reviewed, so there may be flaws in their methodologies or calculations that have yet to come to light. But as far as we can tell now, with the possible exception of New York, there is no reason to believe that any US city is close to achieving herd immunity.

Our office now offers a Covid-19 antibody test (performed by Quest Diagnostic Labs). I will offer it to my patients, but as I explained in my last post, the test will be more useful as a broad measure of community antibody prevalence than to help any individual patient make any decision.

So the novel coronavirus might end up being contained through social distancing and herd immunity and other traditional public health measures, as SARS was contained in 2003. Or it might be eradicated through a massive vaccination program as smallpox was. But these outcomes will not happen soon, certainly not in the next year. Or, like common colds, the novel coronavirus may mutate and continue to circulate globally and evade our grasp.

This tremendous uncertainty about the final goal must inform how we approach the first question. What next?

The LA County “safer-at-home” order has been extended until May 15. Different localities, faced with different numbers of cases, different economic pressures, and different healthcare capacities are making different decisions about when and how to allow people to reopen businesses. The debate about whether to “reopen the economy” has generated much heat but little light. The debate presupposes that it was the government that shut down the economy. It wasn’t. It was the customers. Customers stopped going to restaurants before the stay-at-home orders were given in most states. And they will likely stay away long after the restrictions are lifted. There is no valve labeled “Economy” that someone in Sacramento or Washington can turn to get everyone back to work.

Economies will restart in fits and starts from the bottom up, with every state, city, and family making decisions and balancing risks in a way that fits their particular circumstances. Some states are lifting restrictions now, and some are not. Some colleges have pledged to return to on-campus instruction in the fall, and some will continue online instruction in the fall. And that’s as it should be. There is no reason to expect, say, an older successful urban couple to make the same decision as a twenty-something poor rural couple. The first couple has much to lose by being exposed to coronavirus and little to lose by isolating at home. The second couple might have no alternative but to return to work. And the probability of infection and the consequences of infection would be much lower for them.

This embrace of radical localism will require all of us to reject the extreme arguments on both sides of the debate. On one extreme are those who assert that economic matters are irrelevant and that the shutdown should last until a vaccine or some effective treatment is found. They assert that when lives are at stake, no economic toll is too great. The biggest flaw with this position (and there are many others) is that making everyone poorer will make more people die of other things. Poor people die of chronic illnesses at a much higher rate than rich people. That’s because patients with chronic illnesses frequently benefit from expensive new medications, lifestyle modifications, and logistical support that consume a lot of resources. So if we make everyone poorer by keeping businesses shuttered we’re not simply trading dollars for lives. At some point we’re trading future lives lost to diabetes, heart disease, stroke, and depression for lives saved now from coronavirus.

Those on the opposite extreme assert that the novel coronavirus is no worse than a bad flu, that our reaction to it is exaggerated, and that any further economic toll is unjustified given the tiny death rates in the majority of the country. The biggest flaw with this position (and there are many others) is that the economic toll has been largely dealt by customers, not governments. In a city in which cases and deaths are climbing and hospitals are overwhelmed, very few people will go to movie theaters regardless of whether the economy is officially “reopened”. What may persuade them to go to movie theaters is declining case counts and available ventilators. So managing the pandemic is a prerequisite of, not a competing priority to, reopening the economy.

Given that our understanding of the novel coronavirus is in its infancy, and given that our projections of the consequences of various actions are based entirely on mathematical models that may be entirely unreliable, we should approach local experimentation with some humility. Rather than heap scorn on localities that try a different approach, let’s study their data and learn from their experience. No one knows how to keep the ICUs from filling up while letting people try to make a living. So let’s stop pretending we know.

The best we can hope for is to muddle through, learn from each other, keep a close eye on the local daily case counts, and apparently hoard toilet paper and canned food. Which reminds me. If an armed motorcycle gang comes to your door to recruit you, don’t try to impress them with your unicorn henna tattoo.

Learn more:

More L.A. County Residents Likely Infected With Coronavirus Than Thought, Study Finds (Wall Street Journal)

USC-LA County Study: Early Results of Antibody Testing Suggest Number of COVID-19 Infections Far Exceeds Number of Confirmed Cases in Los Angeles County (LA County Dept of Public Health)

COVID-19 Antibody Seroprevalence in Santa Clara County, California (medRxiv)

Reopening Has Begun. No One Is Sure What Happens Next. (New York Times)

Do Lockdowns Save Many Lives? In Most Places, the Data Say No (Wall Street Journal opinion)

Governor Newsom Outlines Six Critical Indicators the State will Consider Before Modifying the Stay-at-Home Order and Other COVID-19 Interventions (Office of Governor)

My previous posts about the novel coronavirus:

Testing, Testing Part 2

Of Masks And Meaningful Measures

Updates From The Socially Distant

Testing, Testing

Novel Coronavirus FAQ Part 2 – Pandemic Hullabaloo

Coronavirus Frequently Asked Questions

Community Transmission Of Novel Coronavirus In LA County

What You Need To Know About The Novel Coronavirus