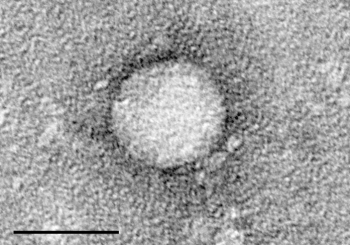

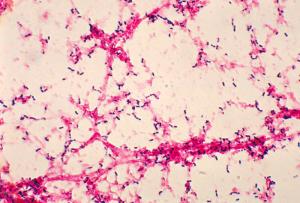

The scale bar is 50 nanometers. Photo credit: Wikimedia/Rockefeller University

In the contest to get a creative name, few pathogens have done worse than hepatitis C. In the 1970s there were two known viruses that caused hepatitis – liver inflammation. You might have already guessed that these two viruses were called hepatitis A and hepatitis B. It was known at that time that people sometimes developed hepatitis after blood transfusions and that the majority of those patients tested negative for hepatitis A and B. A new pathogen was hypothesized and called non-A-non-B hepatitis. It wasn’t until 1989 until the virus was isolated and named [drum-roll please] hepatitis C.

Hepatitis C is transmissible through contact with blood. Before the advent of routine testing of the blood supply it was transmitted through transfusions. It is still transmitted through the sharing of drug and tattoo needles and, in less developed countries, through the reuse of unsterilized medical equipment. Hepatitis C can cause liver failure and liver cancer. There are over 3 million people in the US who are infected with hepatitis C. It is the leading cause of liver transplantation and liver cancer in the US.

There are vaccines against hepatitis A and B, but none yet for hepatitis C.

For decades the standard therapy for hepatitis C has been a regimen including interferon and ribavirin. Interferon has to be given by injection and can have debilitating side effects. A course of treatment lasts 6 to 12 months, and many who begin a course are unable to tolerate it. Fewer than 50% of patients who are treated with this regimen have a meaningful benefit. Because of the length and difficulty of the treatment many hepatitis C patients are thought to be poor candidates and never are offered treatment.

Most of my posts are about a new interesting study, but this post is about a whole crop of studies published in the last two months in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) about the safety and efficacy of novel treatments for hepatitis C. (For links to the individual studies, see the right sidebar of this related NEJM editorial.) Eight recent studies have examined several new medication regimens with truly remarkable results.

The new regimens involve oral medications, so injections are unnecessary. Rather than lasting 6 to 12 months they last 8 to 12 weeks. They are very well tolerated with fairly mild side effects. Best of all, over 90% of the patients appear to have complete clearance of the virus. These results suggest that these medications are no longer in the realm of treating hepatitis C. Instead, for most patients, these medications are a cure for hepatitis C.

Of course, there’s a catch. The medications are astronomically expensive. One of the medications (sofosbuvir) costs $84,000 for a 12 week course. This has caused much consternation and bloviating about pharmaceutical corporate greed. (I’m fascinated by articles that rhapsodically praise the extraordinary medical and scientific breakthrough that these medications represent and a few sentences later vilify the companies that made those breakthroughs possible.)

If we keep our cool and do absolutely nothing, the prices will eventually drop. Competition from newer medications, expiration of patents, and negotiations with insurers will all drive prices down over the next several years. Remember, cell phones and cars were wildly unaffordable when they were new. If we all get angry and insist on making these medicines “affordable” by legislating that insurers cover them, we could make sure that their prices stay astronomic forever.

The exciting news is that within a decade or two we might be able to eradicate hepatitis C. Then maybe we can concentrate our resources on viruses with cooler names, like MERS and Ebola.

Learn more:

New Drug Combination Highly Effective For Hepatitis C (Forbes)

Eradication of hepatitis C on the horizon (The Washington Post)

A Costly Cure for Hepatitis C (The Medical Letter blog)

Therapy for Hepatitis C — The Costs of Success (NEJM editorial, by subscription only)

Therapy of Hepatitis C — Back to the Future (NEJM editorial, free without subscription. The right sidebar has links to all the recent studies of drug trials for hepatitis C.)

In 1996 a naturopath published “Eat Right 4 Your Type”, a diet book purporting that people with different blood types would benefit from different diets. There are a lot more people who want to lose weight than who want to exercise skepticism, so the book became a multi-million dollar success.

In 1996 a naturopath published “Eat Right 4 Your Type”, a diet book purporting that people with different blood types would benefit from different diets. There are a lot more people who want to lose weight than who want to exercise skepticism, so the book became a multi-million dollar success.